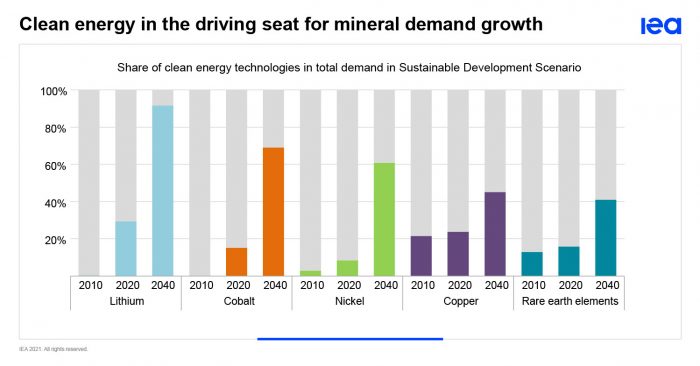

Over 3 billion tons of minerals and metals will be required to meet the growing demand for clean energy technologies. By 2050, the production of critical minerals such as graphite, lithium, and cobalt could increase by nearly 500%. If the Paris Agreement goals are met, the International Energy Agency estimates clean energy technology will drive significant demand growth for minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel, copper and rare earth elements.

While a green energy transition may bring new opportunities for resource-rich developing countries, much depends on variables related to evolving technology and material substitutions. Regardless, increased demand is raising expectations that critical minerals could be the “new oil.” There is also the added pressure for governments to make up budget shortfalls from declining oil and gas revenues.

Latin American countries host many of the resources needed for the energy transition, including lithium, copper, and nickel. As examined below, policy-makers in the region are already advancing policies to help their countries benefit from critical minerals.

Promoting Downstream Processing

Latin American countries are exploring ways to increase the economic benefits from mining, including through downstream processing of critical minerals. Peru’s new law declares the industrialization of lithium a “public necessity.” In Argentina, government officials and other stakeholders signed a memorandum of understanding to build a lithium battery plant. And there is a push from civil society organizations in Chile to grow its copper processing operations. In Mexico, government officials are discussing lithium nationalization.

These countries expect that adding value to raw materials will generate higher export revenues and taxes, as well as positive economic developments such as new jobs and skills for workers. There are some examples of success. In Malaysia, the national oil corporation, Petronas, started an oil refinery in 1983. By 2012, downstream activities contributed over 40% of the company’s revenues. In mining, Botswana’s policy helped it successfully move beyond extraction in the diamond supply chain.

However, policies to promote downstream processing can come with challenges. These operations require large capital investments, suitable locations, as well as reliable and inexpensive energy access. As such, it may be difficult for some countries to develop competitive industries. In Malaysia’s case, Petronas enjoyed access to good infrastructure and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) market. Botswana established dedicated institutions to provide the necessary infrastructure for downstream work and a specific commercial framework to make the polishing industry viable.

Latin American countries are also considering the development of regional supply chains in parallel to the national initiatives to develop industrial capacities. “There is interest from Brazil to import minerals from Latin America and collaborate in the industrialization chain. Brazil is in the transition to low-carbon energy and this is a good opportunity to strengthen relations with neighbouring countries as well as to jointly develop new technologies,” said Enir Sebastião Mendes, Director of the Department of Mineral Transformation and Technology, Ministry of Energy and Mining, Brazil.

Thinking strategically and drawing from lessons learned will be important to develop Latin America’s competitive advantage in the production and processing of critical minerals.

Reviewing Mineral Royalties

Chile is considering a bill that would introduce revenue-based, sliding scale royalties on copper and lithium. The royalty rate will adjust with mineral prices. It is a significant departure from Chile’s current mining tax system, which centres on taxing operating profits (“Special Mining Tax”). The country is looking to benefit from high copper prices. However, the prospect for this reform are uncertain after Chilean lawmakers postponed voting on the bill in August. In Peru, the government is seeking to benefit from recent high-grade lithium and uranium discoveries. Policy-makers proposed a fixed-rate profit-based royalty of 10% on lithium and uranium earlier this year. It was previously a variable rate ranging from 1% to 12%. These two proposals reflect different approaches to achieving the same goal: to capture more income from critical minerals extraction.

Chile’s proposal aims to track mineral prices, increasing the government’s share when prices are high and reducing the burden on investors when prices are low. In this sense it is progressive, like the Special Mining Tax, but with the advantages of being paid earlier and as well as easier for the government to collect. The challenge for Chile will be setting the rates. If set too high, investment may be discouraged and diverted to alternative minerals.

Unlike Chile, Peru has chosen to stick with its profit-based royalty, but at a fixed rather than variable rate. This will improve revenue stability (the government is guaranteed 10% of the profits) and lower the administrative burden of implementing a variable rate. However, profit-based royalties tend to be harder to collect and easier for companies to avoid. Additionally, a fixed-rate royalty may affect investment decisions as it does not adapt to fluctuating profitability.

Auctioning Mining Rights

Colombia and Brazil recently started using auctions to award mineral exploration licences for copper and other minerals. This is a change from the usual first-come-first-served approach seen in the sector. Whereas auctions have been widely used in oil and gas, they are less common in mining, partly due to limited geological information that has made it difficult to accurately price mining projects.

Auctions have the potential to maximize revenues for the host country. Bidders are often required to compete on royalty rates, state equity shares, and pay signature bonuses if they are successful. The main challenge to auctioning mineral deposits is having sufficient geological information to design a competitive tender. Colombia bases its auctions on data made available by the Colombian Geological Survey and the National Mining Agency, while Brazil is auctioning previously approved mining projects that have returned to the National Mining Agency for various reasons, such as a rejection of application or expiry of titles. Another factor is the quality of the resources. It may be easier to attract bidders to compete if the geology is good.

Thinking Ahead

As the transition to clean energy technologies pushes critical minerals to become the “new oil,” Latin American policy-makers are taking various actions to capture potential benefits. The policy tools discussed here each have important strengths and weaknesses to consider. Regardless of the type of policy, Latin American authorities need to strengthen governance frameworks on critical minerals and be guided by past experiences—from both within Latin America and beyond—to craft policies that facilitate good governance and promote transparency, accountability, and independent institutional oversight.